Name: Joshua Cutchin

Occupation: Researcher, Author

Relevance (Aurora): Paramania*

Other Information:*

Contribution:

“I had the distinct pleasure of visiting the Aurora Cemetery in April of 2016 on a day when—in the words of Guy Clark, one of my favorite Texans—“the sun was hot and the dust rose up like smoke.” I was in the company of a cadre of new acquaintances whom I now call old friends, and our guides that day were nothing short of spectacular: noted author Jim Marrs and Daniel Alan Jones.

Together, they looked like a wizard and his apprentice. Jim’s reputation preceded him; I didn’t know anything about this other fellow. I blame that on my own naiveté, as in 2016 I was quite new to the field. Daniel knew his stuff every bit as much as Jim did. In the years since, it’s been a distinct pleasure to watch Daniel, whom I now count as a thoughtful, enthusiastic researcher of the finest caliber.

I digress. We’re talking about Aurora. I listened, wild-eyed, as these two characters expounded upon the history of the crash, of which I only knew the barest bit. I still don’t know as much as I should—not as much as Daniel, few do!—but my thoughts on exactly what it represents have changed in the intervening years.

What do we make of an alleged crash in Texas in 1897? Most people assume Roswell was the first. It wasn’t, nor was it the last, nor was Aurora the first. I suspect that, the further we look back in time, the more these inflection points will crop up. This partially informs where I now stand on the matter.

For those unfamiliar with my approach, I tend to view these phenomena primarily from a psychosocial angle. This doesn’t mean I’m a skeptic. To the contrary. I staunchly believe that something strange, numinous, dare I say ‘non-human,’ lingers beyond the edges of our perception. But when it comes to UFO crashes, I generally think they don’t happen the way most folks believe. Yes, there may have been actual collisions; yes, debris may have been recovered; yes, we might even find bodies from time to time. But I’ve yet to be convinced that these things have any substantive existence beyond the moment itself. “If a UFO crashes in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

I’m aware it’s a strange needle to thread. Allow me to clarify. Hopefully I’ll shed some light on my feelings towards Aurora as well.

I believe that these events, whatever they may be, are closely tied to ourselves. I believe—how anthropocentric of me—that their primary purpose is to bring our species back into right relation with the mythopoetic substrata of our reality. This, in my opinion, is why you will find flying saucer crashes well before Aurora and well after Roswell. It’s a part of our existence, no different from the wind, the sunrise, or the change of seasons. As for the physical material itself, I sometimes wonder if these artifacts don’t have more in common with saints’ relics and fairy flags than extraterrestrial technology. They seem real enough, but they always carry the whiff of fraud, forcing them to linger in that liminal zone between proof and belief.

The question then becomes why Aurora matters at all if it’s merely another inflection point among many. To me, Aurora stands out because, despite all the steampunk trappings of the Airship Wave that gripped our planet in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it still carries all the hallmarks we associate with contact long before and long after. It is remarkable not because it is unique but because it is rote. And I mean that as a compliment.

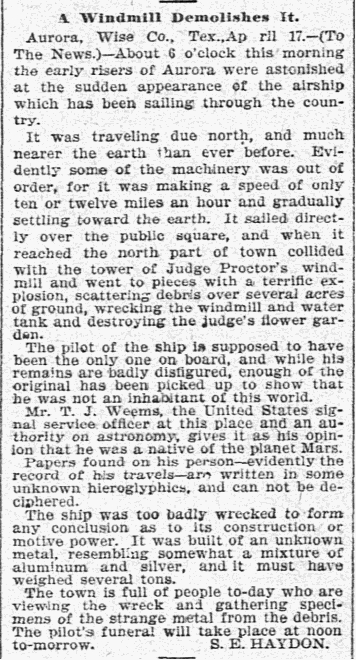

So many details about the Aurora case are echoed in subsequent crashes: whispers of strange metal emblazoned with arcane hieroglyphics, a debris field strewn across the crash site, the titillating allure of an alien body. The Aurora event—whatever its objectively “real” status—may not have originated this script, but the same beats are hit practically every time we hear about subsequent crashes. In some ways, the Aurora crash is the “Mount Sinai” moment of the Airship Wave. Something was handed down to us from above.

The question—one skeptics love bandying about—is whether or not the Aurora crash influenced these newer narratives. A similar question gets asked as well: did older narratives inform the “fictional” Aurora event? I would adamantly deny either possibility. The notion that Jesse Marcel, Sr., picking through debris at Roswell, was familiar with the details of the Aurora incident seems laughable to me in a pre-Internet era. Yet all the beats remain the same.

What does this mean? It means that Aurora, like Roswell, was a moment that touched upon that mythopoetic fiddle faddle I mentioned earlier. For whatever reason, archetypes emerged that day in 1897, bubbling to the surface like a chain of islands above the ocean, always underpinning everything yet rarely glimpsed. Until, of course, it—whatever it is—decides to touch us. To touch humanity. To let the mask slip, so we can peek under the hood at the source code of reality. (How’s that for mixing metaphors?)

I can’t help but frame the Aurora event within this context. Even the name of the town itself is dripping with symbolic meaning. “Aurora”: dawn, enlightenment, the identified flying object of ribbon-like green and red hues flashing through the night. Emissaries of the sun. Extraterrestrials, choosing a place to crash their flying saucer, could not have picked a more fitting landing site.

I believe something happened in Aurora, Texas. I just think it might have been stranger than aliens.”

– Joshua Cutchin